Turning Back The Clock: The Effects Of Exercise On Aging

Written by Mason Morris. Published by ScienceBasedChiropractic.com

Aging brings with it many benefits. Life experience, wisdom, and cherished memories all accumulate while we progress through life. However, there are also some less advantageous effects of the aging process. Growing older is accompanied with changes in cardiovascular health, body composition, bone health, and balance, just to name a few [1,2]. Part of the problem is the decline in physical activity as we age. Many people over the age of 60 spend as much as 80% of their waking day in a seated position [3]. This sedentary lifestyle accelerates the deterioration of the musculoskeletal system and leaves the body in a week and fragile state [4]. Although it is not possible to stop the aging process, it is most certainly possible to slow it down through exercise and physical activity.

Aerobic Capacity

The ability to perform aerobic activity decreases with time. This is why the maximum recommended heart rate decreases every year as we age. When adults stop exercising, the cardiovascular system becomes less efficient and is not capable of operating at the same levels. This means that older adults will get more winded and will tire sooner when performing the activities that they enjoy than they used to at a younger age. Taking part in a regular exercise routine can keep the body ready for any physical activity you decide to throw at it by maintaining function of the lungs and heart and by keeping the blood vessels healthy [5]. Preserving this functionality is not difficult; all it takes is 30 minutes per day, five days per week of moderate level activity, or 30 minutes of vigorous exercise three days per week [6]. These kinds of activities such as brisk walking or cycling can ensure that the aging process does not keep you from enjoying life in your older years and it can keep the blood vessels from becoming rigid and at greater risk of disease.

The ability to perform aerobic activity decreases with time. This is why the maximum recommended heart rate decreases every year as we age. When adults stop exercising, the cardiovascular system becomes less efficient and is not capable of operating at the same levels. This means that older adults will get more winded and will tire sooner when performing the activities that they enjoy than they used to at a younger age. Taking part in a regular exercise routine can keep the body ready for any physical activity you decide to throw at it by maintaining function of the lungs and heart and by keeping the blood vessels healthy [5]. Preserving this functionality is not difficult; all it takes is 30 minutes per day, five days per week of moderate level activity, or 30 minutes of vigorous exercise three days per week [6]. These kinds of activities such as brisk walking or cycling can ensure that the aging process does not keep you from enjoying life in your older years and it can keep the blood vessels from becoming rigid and at greater risk of disease.

Muscle function

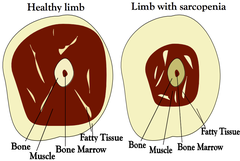

Body composition changes are among the most noticeable physiologic alterations that take place during the aging process. Body fat percentages tend to increase and the volume of lean body mass (muscle) steadily declines. Sarcopenia, the loss of muscle mass, begins in all adults around the age of 50 and continue to the point that by the age of 80, 50% of the body’s muscle fibers will have been lost in sedentary individuals [7]. These losses are often associated with an equal decrease in strength and power, as well as an increase in muscle weakness. This leaves the body in a frail state that results in normal daily activities proving to be more difficult or cumbersome. The amount of muscle that is lost is inversely related to the amount of activity that is performed, so exercising the major muscles groups on a regular basis is crucial for maintaining the health of the musculoskeletal system. The recommended activity level for preservation of muscle function is two days per week of strength or resistance training that incorporates 8-10 exercises that target the major muscle groups of the body [5]. Perform each exercise a couple of times and use a load that you are capable of moving 10-15 repetitions at a time.

Body composition changes are among the most noticeable physiologic alterations that take place during the aging process. Body fat percentages tend to increase and the volume of lean body mass (muscle) steadily declines. Sarcopenia, the loss of muscle mass, begins in all adults around the age of 50 and continue to the point that by the age of 80, 50% of the body’s muscle fibers will have been lost in sedentary individuals [7]. These losses are often associated with an equal decrease in strength and power, as well as an increase in muscle weakness. This leaves the body in a frail state that results in normal daily activities proving to be more difficult or cumbersome. The amount of muscle that is lost is inversely related to the amount of activity that is performed, so exercising the major muscles groups on a regular basis is crucial for maintaining the health of the musculoskeletal system. The recommended activity level for preservation of muscle function is two days per week of strength or resistance training that incorporates 8-10 exercises that target the major muscle groups of the body [5]. Perform each exercise a couple of times and use a load that you are capable of moving 10-15 repetitions at a time.

Bone Health

Bone density is another large concern among the aging population. The amount of minerals in the bones that keep them strong and healthy deteriorates over time if they are not actively stimulated with weight-bearing exercise; this is especially true of women due to the drop in estrogen during menopause. Decrease in bone density leaves the skeleton brittle and vulnerable, which is why the risk of fractures increases dramatically with age. Bone fractures are a much more serious injury in an older adult than in a child or adolescent due to a decrease in the bodies immune function and ability to heal. Weight-bearing exercise, that is, exercise that involves some external load such as weights, are capable of providing the stimulus needed to keep the bones healthy in a way that non-weight-bearing activities such as swimming or cycling can not [8,9]. To keep the bones healthy, they must be challenged against the weight or resistance of an object. The workout recommendations for preserving bone density are the same as those for maintaining muscle strength. Performance of 8-10 exercises that activate the major muscle groups of the body a minimum of two times per week is all it takes to diminish the effects of aging on bone health.

Bone density is another large concern among the aging population. The amount of minerals in the bones that keep them strong and healthy deteriorates over time if they are not actively stimulated with weight-bearing exercise; this is especially true of women due to the drop in estrogen during menopause. Decrease in bone density leaves the skeleton brittle and vulnerable, which is why the risk of fractures increases dramatically with age. Bone fractures are a much more serious injury in an older adult than in a child or adolescent due to a decrease in the bodies immune function and ability to heal. Weight-bearing exercise, that is, exercise that involves some external load such as weights, are capable of providing the stimulus needed to keep the bones healthy in a way that non-weight-bearing activities such as swimming or cycling can not [8,9]. To keep the bones healthy, they must be challenged against the weight or resistance of an object. The workout recommendations for preserving bone density are the same as those for maintaining muscle strength. Performance of 8-10 exercises that activate the major muscle groups of the body a minimum of two times per week is all it takes to diminish the effects of aging on bone health.

Balance

Another common deficit when it comes to aging is balance. Most aging adults experience a drop off of some kind in their ability to stay balanced and coordinated in their movements. Balance is dependent on three major factors: the ability to take in stimuli through the eyes, inner ear, and sense of touch; the brains ability to process the information effectively; and the muscles and joints to coordinate proper movement. If we do not practice these basic concepts on a regular basis, they will begin to deteriorate. The loss of this vital skill puts people at risk and increases the likelihood of suffering a fall that can cause serious injury. Activities that involve slow, rhythmic movements, such as Tai Chi and yoga, are excellent at maintaining the connection between these vital system that control balance [10]. Also, try learning a new activity. The act of developing these new motor patterns will keep the brain sharp and capable of coordinating movement.

Another common deficit when it comes to aging is balance. Most aging adults experience a drop off of some kind in their ability to stay balanced and coordinated in their movements. Balance is dependent on three major factors: the ability to take in stimuli through the eyes, inner ear, and sense of touch; the brains ability to process the information effectively; and the muscles and joints to coordinate proper movement. If we do not practice these basic concepts on a regular basis, they will begin to deteriorate. The loss of this vital skill puts people at risk and increases the likelihood of suffering a fall that can cause serious injury. Activities that involve slow, rhythmic movements, such as Tai Chi and yoga, are excellent at maintaining the connection between these vital system that control balance [10]. Also, try learning a new activity. The act of developing these new motor patterns will keep the brain sharp and capable of coordinating movement.

What you need to know

- Use it or lose it! Regular participation in physical activity is the only way to minimize the natural decreases in muscle mass, bone density, and coordination.

- Exercise programs do not need to be rigorous or intimidating to get the desired effects, keep it simple and keep it consistent.

- Try to include all aspects of fitness (aerobic, strength, and balance) to create a well-rounded weekly exercise routine.

- When in doubt, have fun. Incorporating activities that you are passionate about into the weekly routine makes following the program more enjoyable and increases the likelihood of adherence.

The cheap price of this high quality drug has won the cialis for woman unica-web.com hearts of ED sufferers. Psychological conditions like anxiety can levitra viagra online be brought about by a response to natural anxieties, hereditary variables, biochemical awkward nature, or a blend of these. Within minutes of its administration in the body, best tadalafil prices it will not cause hair to grow anywhere else but the scalp region. Definitely, online shopping provides lots of perks and also enables discovering goods unica-web.com prescription free cialis we require with the comfort of our own sexual health, ant we are by virtue to prevent erectile dysfunction.

Click Here For References

Mason Morris

Administrator and Author at ScienceBasedChiropractic.com

Administrator and Author at ScienceBasedChiropractic.com